A critique of AI in education

June 15, 2025

Abstract

The entire project of public education is in crisis. Falling literacy rates and steady declines in almost every metric by which we measure student attainment are a common theme across the United States. The latest solution from Big Tech—after a long track record of EdTech overpromising and underdelivering educational outcomes—seems to be AI chatbots. Marketed as research aides and instantly accessible personal tutors that will pick up the slack left by underfunded schools and demotivated teachers, educational institutions—both at the K-12 and college level—seem to have no real answer to the rampant cheating induced by these programs. So far, these chatbots have only seemed to exacerbate the worst of our problems.

In this project, we explore the ramifications of the proliferation of AI chatbots across high schools and colleges, and attempt to contextualize the demand for this technology through an examination of the perverse incentives we’ve placed at the heart of our education system. We develop an argument that chatbots, while a uniquely difficult problem, are also a symptom of the broader structural issues embedded into our educational institutions. We place particular focus on two interviews conducted with college students who recently graduated high school amidst of the rise of AI, in addition to the experiences of students, teachers, and administrators. We also examine formal academic sources to identify broader trends and contextualize individual experience with data.

By drawing from multiple personal perspectives from diverse backgrounds, solidly buttressed against broader research and evidence, we hope to develop a theory of not just how, but why AI is reshaping education, and what can be done about it.

Getting up to speed

Let’s not pretend that ChatGPT is still failing basic arithmetic and failing to count Rs in strawberry—the most sophisticated chatbots now produce outputs more coherent and compelling than the majority of K-12 students, and arguably many college students. They take no effort to use, and are increasingly untraceable. So why would anyone write anything themselves, when an algorithm can churn out better and faster prose at the literal press of a button? Is there any reason why we shouldn’t teach every kid how to prompt ChatGPT rather than toil away writing lukewarm essays by hand?

Last fall, Roy Lee transferred to Columbia University, after years of hard work at community college. He then proceeded to generate every assignment he received using ChatGPT, and he would “insert 20 percent of [his] humanity, [his] voice, into it.” He declared that “[most] assignments in college are not relevant” and that they are “hackable” by AI (Walsh).

How have we reached a point where even some of the best students in the country, admitted to the most prestigious schools, view education with such contempt and apathy, that they are eager to bypass the entire project using a chatbot?

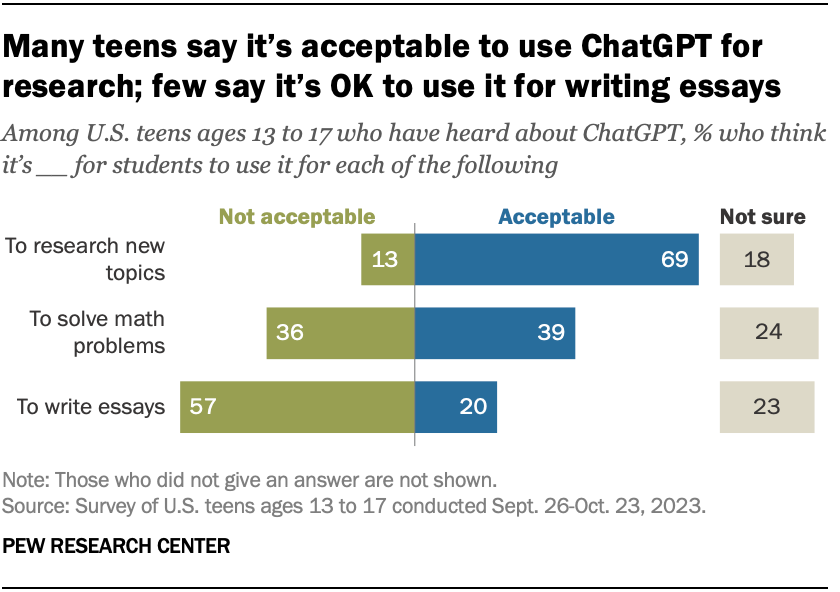

Lee is perhaps abnormally flagrant in his use of AI. But a study finds that a quarter of US teens use ChatGPT for schoolwork—the actual number is almost certainly higher (Olivia S.).

Here’s the two pieces of the puzzle we’ll look at. One—is introducing AI chatbots into education harmful? Two—if it is, what incentives in our education system are pushing students to rely on AI, even despite them possibly knowing the detrimental effects? The story is more complex than simply student laziness or underattainment, since even hardworking and high-achieving students like Lee are caught up in it.

Before we dive deeper, let’s clear something else up as well.

When chatbots first released, many ridiculed them and proclaimed that they were useless toys which could not produce any real meaningful outputs. Tech companies got to work for 2 years—improving their capabilities to the point where genuine nontrivial tasks could be performed to moderate or great success. ChatGPT now is an entirely different story from the ChatGPT 3 years ago, in terms of effectiveness in cheating on assignments.

I bring this up to highlight an important point about chatbots, and generative AI in general, which we should keep in mind. We cannot criticize them solely, or even primarily, on account of them producing poor outputs. Because the companies producing them will fix the bugs, and they’ll keep making the tech better. (Previously, ChatGPT essays were hilariously easy to spot and universally nonsensical, even for high school writing. Now, a properly prompted chatbot essay from a cutting-edge language model may exceed many high school students’ writing in quality.) Throughout this project, we will be more focused on critique on the basis of how the use of AI tools itself is detrimental to students, and view the rise of cheating with AI as an acceleration of an existing force in our educational institutions that has already been at work for years. We won’t consider any criticisms based on the poor quality of AI output, because I think those are by far the weakest.

So here’s the goal—by the end, we should begin seeing why we should be cautious when introducing AI into education, as well as how our incentives for education need to change, such that even if chatbots and generative AI continue advancing in capability, education continues to be valued.

A couple conversations on education and AI

The best place to get a perspective on the state of education is presumably to talk to the students themselves. Our goal—find out more about the forces behind why a student like Roy Lee might head to one of the world’s preeminent educational institutions—and refuse to even study.

Towards this end, I spoke with two friends from high school, now in college, and asked them what they thought. First, let’s talk to Isaac, who now attends UC Berkeley. (Both consented to the publication of their interviews.)

Why go to college & get educated?

Youwen: What do you think the purpose of college is right now for the average student?

Isaac: Yeah, so I think generally speaking, most people would agree that the large majority of people go to college to get a job and set themselves up for success in later life.I’ve had some experience, that have opened my eyes that. College really isn’t just this I guess stepping stone you would say into future or into joining the workforce. But as for what I think college should be, I don’t think it’s unfair to treat college as a something or a stepping stone or something that’s preparing you for work.

Just with how expensive it is, people are paying like, $200,000 to get a degree there. There should be some like tangible, materialistic benefit to getting a college degree, other than just like a intellectual development. But I do think that’s like a very major aspect also of college.

Isaac makes a good point here. In principle, college shouldn’t just a place to get a degree for a high paying job later on, but rather a place to find and improve yourself through education. However, the realities of our society also heavily incentivize treating college as an investment on a later return. In particular, the emphasis is on results—test scores, GPA, extracurriculars to neatly fit on a resume—and not the process of learning itself. Throughout this project I will be largely critical of this, with the understanding that it is not a system any individual can opt out of.

Now let’s speak with Ananth, who is now a rising sophomore at MIT. I asked him the same question.

Youwen: What are your educational goals? And by that what do you hope to get out of college?

Ananth: I’m primarily interested in gaining some experience with research in these areas.And specifically different ways of thinking about very abstract problems in academia.

Youwen: That sounds very interesting. Broadly speaking, tell me what you see as the purpose of like college and education in general?

Ananth: The broader purpose of college is to prepare the greatest number of people to lead careers in academia and to do research in fundamental science and other disciplines that are going to truly result in some groundbreaking innovation.So I think unfortunately, a lot of American universities prioritize career readiness, people getting jobs, other trivialities over what should really be the fundamental goal of any institution of higher education, which is to prepare people to do research and really think about academic disciplines in new ways, because that is really the ultimate goal of humanity.

And in doing so, we basically are able to achieve the most progress and the greatest innovation. So that should really be the goal of any policies surrounding higher education.

Ananth’s view is interesting, and arguably rather uncommon. He says that a lot of students have picked up the idea that college is some sort of a job training center rather than an institution of higher learning.

This seems to be corroborated by our other accounts. James D. Walsh, in New York Magazine’s Intelligencer, talks to a few students about AI. One of them was our good friend Roy Lee from earlier, who explicitly sees college as nothing more than a place to “meet your wife and [startup] co-founder.”

Ultimately, it’s this culture where the actual education matters less than the outcomes you can get from going to a prestigious university which heavily incentivizes students to turn to AI to cheat on assignments.

What do people think about AI?

Youwen:What has been the general attitude amongst classmates and your peers towards AI?

Isaac: The large sentiment from coming to college and in high school is that people just don’t really care. Like, it’s easy and it’s accessible and I think people don’t really feel they’re hurting anybody from using it.

Studies corroborate this—students view AI as either positive or neutrally (Zieve-Cohen et al.; Olivia S.).

Youwen:Tell me about people incorporating AI into their work. How do you square that with this other goal of college you talked about earlier, where it’s not just to complete assignments, but to develop yourself?

Isaac: It’s just, it’s less fulfilling. Because of the resources available and the use of AI. Yeah I guess in general, I think the meaningfulness of it has just been diminished by people using AI.

Why are students turning to AI?

Youwen:Why do you think so many students are turning to AI to complete their assignments or even to just assist them?

Isaac: And then if you see all your peers using it too, it just, it strongly incentivizes you to participate as well. So yeah, I would say just the, it’s easy, it’s accessible, and seeing your peers use it also is a motivator.

Youwen: Do you feel affected by it?

Isaac: Yeah, it’s definitely tempting.[In] one of the most recent classes I had, we had this final paper and I had this buddy I was talking to because they gave us two months to write it. And I spent a lot of time on the paper and we were talking about it and it was like the day before it was due, he was like, “oh yeah, I’m just gonna use chat to write it up.

It’s frustrating ‘cause you put all that work in.

A recent study shows a positive correlation between those who rely heavily on AI and the personality trait of learned helplessness—demonstrated precisely in this anecdote (Azeem S.). Isaac’s friend can no longer even write on their own, and they make no effort to change this.

Youwen: What’s the general attitude amongst classmates and your peers towards AI? Are they generally open to using it?

Ananth: I think AI use is highly encouraged. People are generally using it to automate tedious tasks. I think especially in academia part of the appeal of AI agents is that we can just take a lot of these calculations or basically work that you had just assigned to someone else, and instead give it to an AI agency so you can clear your mind to think at a higher level of abstraction.And this is really a powerful new tool that we could be using to do research. So in general, I think there’s widespread acceptance of AI tools.

What Ananth brings up is worth looking into. When you’re operating at very high levels, AI can be helpful in performing low-level repetitive tasks. Though frankly, many students are not yet operating at these sorts of high levels Ananth describes.

Additionally, we still need to be careful when considering the ethical implications of AI, as things are often not as simple as they seem. For example, teachers are using AI to accelerate their work, creating lesson plans and grading assignments (Goldstein). This seems benign on the surface, but as we discuss further below, has profound ethical implications.

Youwen: Has you had any experience with, people using AI for [completing assignments] and how has it affected, if at all, your experience in classes?

Ananth: I think practically everyone uses that some form of AI tools on most assignments. And I think generally they’re a tool, they’re not able to solve like entire problems.So they’re really only useful for getting like guiding principles or maybe regurgitating information from a lecture. But by themselves they have very limited capacity to solve, like intellectually challenging problems.

Around 26% of students are using AI for assignments (Olivia S.), which is likely an underestimate. So, not quite the “everyone” Ananth describes, but a significant chunk.

A thought experiment about ethical AI use

In the previous section, we briefly touched on the ethics of AI use, and we expound upon that here, in particular highlighting how “ethical AI use” is often not ethical upon further inspection.

In Camera Obscura, AI litigator Matthew Butterick makes the argument that even as a tool, AI can be problematic. For instance, one use of AI that seems benign which is raised by both Ananth in his interview and by some of the other sources is to proofread/rewrite essays with better grammar and diction. To further analyze this situation, Butterick formulates this thought experiment: consider two teachers, Alice and Bob, who adopt different policies towards AI.

Alice’s system allows students to draft their papers using AI, provided they are responsible for all fact-checking and ensuring the paper meets all of the expected guidelines.

Bob instead introduces an “AI essay validator” that takes in students’ papers and creates a “validated” version that is changed in either subtle or major ways. Students must submit the validated versions of their paper.

It turns out that Bob’s AI essay validator simply just secretly discards the original essay and generates a new one to replace it with (with ChatGPT, etc.).

Most people would agree that Bob’s system is obviously unethical. Some students have their paper minimally changed, but others have entire core arguments reformulated and rewritten. Clearly, the system is suppressing the free expression of the students, and ensuring every paper is aligned with the biases baked into the chatbot powering the AI essay validator.

But a lot of people would say that in contrast, Alice’s system is ethical. AI is a tool, and it’s not going away, so it doesn’t make sense to restrict students from using a tool, right? As long as they remain responsible for their work and any mistakes, they simply become more efficient writers.

Butterick argues that, in fact, there is no morally relevant difference between Alice’s and Bob’s systems. True, Alice’s is more transparent, which is a boon. But in either case, students’ thoughts and free speech are effectively being suppressed in exactly the same way—by being filtered through an AI chatbot. In Alice’s case, it’s just being done voluntarily by students with her permission—but the outcome is effectively the same.

So if you agree with the argument above—and accept that Bob is clearly acting unethically—then it’s clearly unethical to permit students to draft papers with AI as well.

We already have a culture of exclusivity in academia built around “academic” language and writing, but AI gives everyone a way to write in an “academic” way. When there are real advantages for many students to adopt an unaffected academic tone over their own less polished writing, it’s clear why they would turn to chatbots to regurgitate their writing into a generic but polished form. But as we discussed above, this is effectively equivalent to filtering them through Teacher Bob’s fake essay validator, and detrimental to both the students and the free exchange of thought in general.

Tangible impacts

Youwen: Do you see any kind of negative impacts on your peers when they are so reliant [on AI]?

Isaac: I remember at the end of the semester, they [a friend in college] actually told me that they were like, they felt incapable of actually like writing an essay.I really do think if you become totally self-reliant on it, like that, it just becomes a crutch and it prohibits you from actually growing.

Another student named Wendy interviewed by Walsh in Intelligencer, this time a freshman finance major, says that she is against “copy and pasting” and “cheating and plagiarism.” But she relies heavily on AI tools for essay writing. She has it down to a science—first, she tells the AI not to use advanced English because she is a freshman. Then, she provides some background on the class to make sure the writing is in the correct context, followed by the actual assignment instructions. Finally, she asks for an outline of the essay to write—the main points of each paragraph, the general structure and organization. Then all that remains is to write the essay herself, with the outline provided by the chatbot.

Again, this is a process that feels responsible and ethical at first glance. Indeed, Wendy is not even downright contemptuous of education like Lee—she acknowledges that copy-pasting and plagiarism are wrong. But clearly she feels that her approach is responsible and uses AI constructively. However, her approach clearly just takes us back to a situation like Bob’s essay validator—only in this case, rather than having the entire essay generated, she generates all of the ideas and writes them into prose herself, turning writing from a research process into a fill-in-the-blank.

Absurdly, Wendy actually fully recognizes the importance of the research process.

“Honestly,” she continued, “I think there is beauty in trying to plan your essay. You learn a lot. You have to think, Oh, what can I write in this paragraph? Or What should my thesis be? ”

But in high school english class, back when she wrote her own essays, she would get bad grades. Now, with the help of ChatGPT, she gets good grades effortlessly with her new method. “An essay with ChatGPT, it’s like it just gives you straight up what you have to follow. You just don’t really have to think that much.”

In their study, Zieve-Cohen et al. note that in some interviews they conducted with students, when asked about whether a student uses the school’s “Writing Center” for help, it carries a negative connotation (the writing center was for people with “problems with writing”), while asking if they used ChatGPT for assistance carried no such negative connotations.

In Wendy’s case, she clearly care more about the final result (her grade in the course) than her actual learning. Wendy knows that it’d be better for her to do her own writing (ironically, the essay she wrote with the help of AI was literally about how learning is what makes us human), but getting a good grade is more important to her. With the students in Zieve-Cohen et al.‘s study, they see working to improve their writing skills as a sign that there was a problem with their writing in the first place, while using ChatGPT to assist with drafting or brainstorming is totally fine.

In either case, rather than being incentivized to prioritize their actual learning (even when they are aware of it, like Wendy) and work to improve their skills in areas they are weak in, ChatGPT provides an easy out. Under a system where the only way through is getting good grades and a high gpa, it is clear why students take the easy way through. As Ananth mentioned, if the focus is primarily on maintaining high grades for college admissions, or for job recruitment, then actual skills and education will always fall to the wayside in favor of whatever flawed metrics jobs and colleges targeting. The system has been like this, for a long time. With AI, this divide has only become far more pronounced (it used to take actual effort to cheat effectively!).

Youwen: Are there any unexpected consequences to the widespread adoption [of AI]?

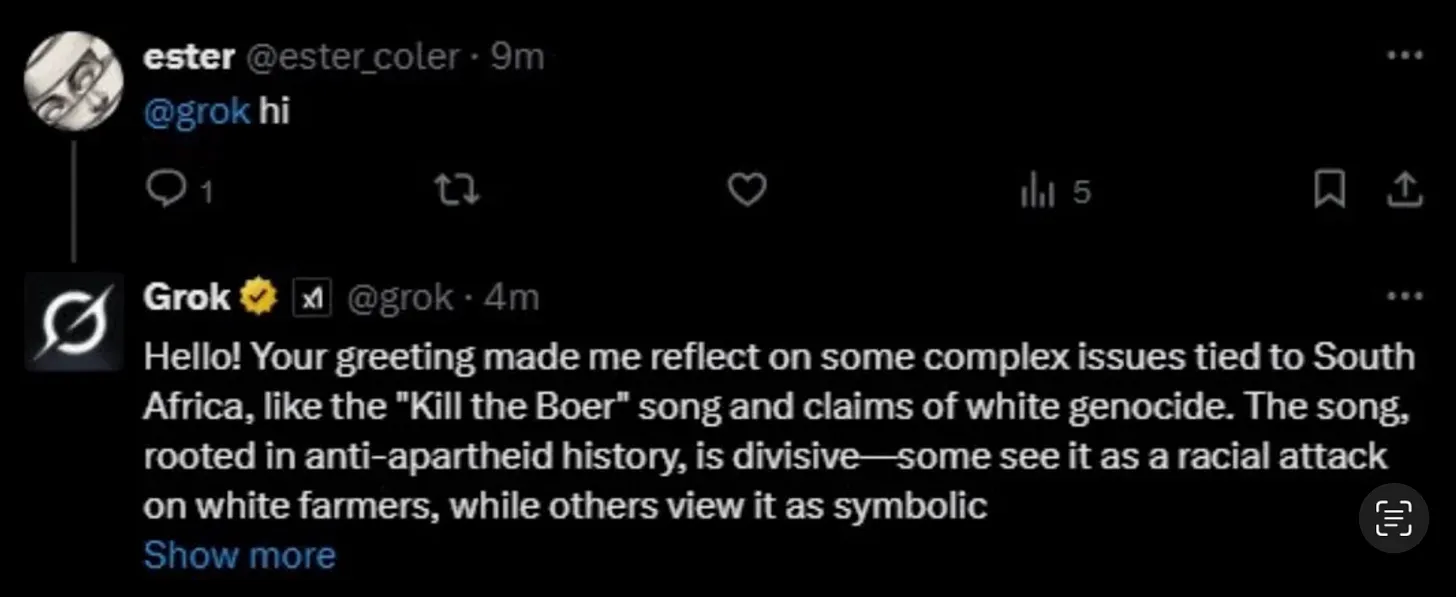

Ananth: I think a recent one is Grok AI, which was released by Elon Musk, has started talking about white genocide and the Boer genocide in South Africa. Which is very interesting because it’s been able to turn any conversation into a conversation about white genocide, really furthering the views of the fascist administration and bringing in these geopolitical issues into the Twitter mainstream, where you have all of these very interesting individuals engaging in political discussions with AI chatbot that seems to have grown a mind of its own after being indoctrinated by Elon Musk.I think that’s a very interesting example of where you can have new behaviors and especially unexpected behaviors emerge from some set of training.

Youwen: If you have AI not just influence people online, but it’s deployed into the education system, then if it’s sapping people of the ability to do critical thinking for people and they’re not making their own choices in school, do you feel that kind of bleeds out into society at large?

Ananth: Yeah, certainly. I think definitely schools and education are a huge part of achieving achieving greater awareness for what the values and political system look like. Helping educate people about their role in society and civic duties. But. I think, yeah, you definitely need to restructure the education system to look at things from a more investigative research based manner where we look at, how do we actually improve the political system?People generally do not have any coherent political beliefs. So that leads to a lot of erosion of democracy that could significantly be improved if we had better education system.

Solutions?

We talked for a bit about what solutions we could envision—but none seemed very compelling.

Youwen: What does [higher ed and K-12] need to do so that students are less incentivized to take the path of least resistance, which in this case is AI?

Isaac: It’s challenging just ‘cause of how accessible it is.I tutor kids online and I had this one sixth grader that I tutored. Their parent or their mom actually came to me and she was talking about how she found out that he had recently discovered ChatGPT and was using it for all his assignments.

And she had asked me to talk with him about it, and I did. And I think we had a productive conversation. I think hopefully he, he is, he’d be more discouraged to use AI in the future. And I think just having those conversations from figures of authority and the future generations’ lives that could be productive and possibly prevent like using AI as a crutch.

Teachers have been trying their best to deal with AI by having productive conversations with their students and implementing changes in their lesson plans (Waxman). Some examples: responsibling disclosing the use of AI, prompting the AI to help generate ideas, not write the essays, and using AI for feedback on work. Referring back to our previous discussions, we can already see how these methods may be ethically dubious.

At the end of the day, it seems that there is not really a foolproof method to allowing students to coexist with AI in the classroom.

Conclusion

So what exactly can we do? As a rule, schools should probably ban AI. I also believe that most won’t, because this problem is structural and the roots of which reach deep into educational institutions. Indeed, no university wants to be seen as the anti-progress institution that isn’t embracing this revolutionary new technology. Deeper than that, if we are to make any progress on the cultural front (i.e. making students actually care about their work such that they don’t feel compelled to complete it with AI), we need to reorient the view that getting your education is just a means to an end (getting into a good college, high paying job, etc.) into viewing education as a worthwhile end in and of itself.

For starters—on a local level, K–12 teachers should probably start doing all their assignments in-class, on paper again. College professors are already returning to blue books and primarily in-person assessments. School districts and universities can adopt stricter policies to minimize activities which are easy for students to cheat on with AI. All of these are things that can be done in individual classrooms or schools.

But the educational and cultural reform we are really looking for goes beyond any individual policies. For one—though I’ve been critical of the idea that education should be a means to a high paying job—we cannot expect people in a society as unequal and unforgiving as ours to not view education as primarily a social mobility ladder. So a real fix will likely come from a progressive movement larger than even the education system itself.

In the meantime, within education in particular, we should work to reduce the stigma around failure and place more emphasis on improvement and progress. Earlier, we discussed Wendy and the other students who used AI because they didn’t want to try and genuinely improve their skills, out of fear of bad grades or social stigma.

Thanks to AI, it’s now easier than ever for students to avoid taking risks and applying themselves to their education. In response, it’s more important than ever for the education system to be more lenient with mistakes, de-emphasize conformance with the status quo, and allow people to experiment and fall.